Magnetic field

| Electromagnetism | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Electricity · Magnetism

|

||||||||||||

A magnetic field is a field of force produced by a magnetic object or particle, or by a changing electrical field[1] and is detected by the force it exerts on other magnetic materials and moving electric charges. The magnetic field at any given point is specified by both a direction and a magnitude (or strength); as such it is a vector field.[nb 1]

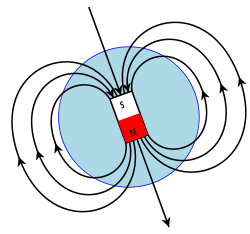

The complex mathematics underlying the magnetic field of an object is usually illustrated using magnetic field lines. These lines are strictly a mathematical concept and do not exist physically. Nonetheless, certain physical phenomena, such as the alignment of iron filings in a magnetic field, produces lines in a similar pattern to the imaginary magnetic field lines of the object. See the figure to the left.

Magnets exert forces and torques on each other through the magnetic fields they create. Electrical currents and moving electrical charges produce magnetic fields. Even the magnetic field of a magnetic material can be modeled as being due to moving electrical charges.[nb 2] Magnetic fields also exert forces on moving electrical charges.

The magnetic fields within and due to magnetic materials can be quite complicated and is described using two separate fields which can be both called a magnetic field: a magnetic B field and a magnetic H field. Energy is needed to create a magnetic field. This energy can be reclaimed when the field is destroyed and, therefore, can be considered as being "stored" in the magnetic field. The value of this energy depends on the values of both B and H.

An electric field is a field created by an electrical charge and such fields are intimately related to magnetic fields; a changing magnetic field generates an electric field and a changing electric field produces a magnetic field. (See electromagnetism.) The full relationship between the electric and magnetic fields, and the currents and charges that create them, is described by the set of Maxwell's equations. In view of special relativity, electric and magnetic fields are two interrelated aspects of a single object, called the electromagnetic field. A pure electric field in one reference frame is observed as a combination of both an electric field and a magnetic field in a moving reference frame. In quantum physics, this electromagnetic field is understood to be caused by virtual photons. Most often this quantum description is not needed because the simpler classical theory is sufficient.

Magnetic fields have had many uses in ancient and modern society. The Earth produces its own magnetic field, which is important in navigation since the north pole of a compass points toward the south pole of Earth's magnetic field, located near the Earth's geographical north. Rotating magnetic fields are utilized in both electrical motors and generators. Magnetic forces give information about the charge carriers in a material through the Hall effect. The interaction of magnetic fields in electrical devices such as transformers is studied in the discipline of magnetic circuits.

History

Although magnets and magnetism were known much earlier, one of the first descriptions of the magnetic field was produced in 1269 C.E. by the French scholar Petrus Peregrinus[2] who mapped out the magnetic field on the surface of a spherical magnet using iron needles. Noting that the resulting field lines crossed at two points he named those points 'poles' in analogy to Earth's poles. Almost three centuries later, William Gilbert of Colchester replicated Petrus Peregrinus' work and was the first to state explicitly that Earth itself was a magnet. William Gilbert's great work De Magnete was published in 1600 and helped to establish the study of magnetism as a science.

One of the first successful models of the magnetic field was developed in 1824 by Siméon-Denis Poisson (1781–1840). Poisson assumed that magnetism was due to 'magnetic charges' such that like 'magnetic charges' repulse while opposites attract. The model he created is exactly analogous to modern electrostatics with a magnetic H-field being produced by 'magnetic charges' in the same way that an electric field E-field is produced by electric charges. It predicts the correct H-field for permanent magnets. It predicts the forces between magnets. It even predicts the correct energy stored in the magnetic fields.[nb 3]

Despite its successes,[nb 4] Poisson's model fails on two accounts. First, magnetic charge does not exist. Cutting a magnet in half does not result two separate poles, but two separate magnets each of which has both poles. Second, it does not account for the remarkable relationship between electricity and magnetism.

The formation of the modern theory of magnetism began with a series of revolutionary discoveries in 1820, four years before Poisson's model was developed. First, Hans Christian Oersted discovered that an electrical current generates a magnetic field encircling it. Second, André-Marie Ampère showed that parallel wires having currents in the same direction attract one another. Finally Jean-Baptiste Biot and Felix Savart discovered the Biot–Savart law which correctly predicts the magnetic field around any current carrying wire.

In 1825, Ampère extended this revolution by publishing his Ampère's law. Like the Biot–Savart law, it correctly describes the magnetic field generated by a steady current but it is more general. More importantly, it help lay the foundation for the full theory of electromagnetism. And, in 1831, Michael Faraday showed that a changing magnetic field generates an encircling electric field and thereby demonstrating that electricity and magnetism were even more tightly knitted.

Between 1861 and 1865, James Clerk Maxwell developed and published a set of Maxwell's equations which explained and united all of classical electricity and magnetism. The first set of these equations was published in a paper entitled On Physical Lines of Force in 1861. The mechanism that Maxwell proposed to underlie these equations in this paper was fundamentally incorrect, which is not surprising since it predated the modern understanding even of the atom. Yet, the equations were valid although incomplete. He completed the set of Maxwell's equations in his later 1865 paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field and demonstrated the fact that light is an electromagnetic wave. Thus, he theoretically unified not only electricity and magnetism but light as well. This fact was then later confirmed experimentally by Heinrich Hertz in 1887.

Even though, the classical theory of electrodynamics was essentially complete with Maxwell's equations, the twentieth century saw a number of improvements and extensions to the theory. Albert Einstein, in his great paper of 1905 that established relativity, showed that both the electric and magnetic fields were part of the same phenomena viewed from different reference frames. (See moving magnet and conductor problem for details about the thought experiment that eventually helped Albert Einstein to develop special relativity.) Finally, the emergent field of quantum mechanics was merged with electrodynamics to form quantum electrodynamics or QED.

B and H

|

||||||||||

|

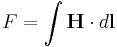

The term magnetic field is used for two different vector fields, denoted B and H.[nb 5] There are many alternative names for both (see sidebar). To avoid confusion, this article uses B-field and H-field for these fields, and uses magnetic field where either or both fields apply.

Outside of a material (i.e., in vacuum) the B-field and the H-field are indistinguishable. (They only differ in their units and magnitudes and not in how they vary with location and time.) It is only inside a material that the difference is important. The B-field depends only on currents (both macroscopic and microscopic such as the movement of electrons around their nuclei), while H depends on the macroscopic currents and a factor that is closely related to the concept of magnetic charge.

The B-field can be defined in many equivalent ways based on the effects it has on its environment. For instance, a particle having an electric charge, q, and moving in a B-field with a velocity, v, experiences a force, F, called the Lorentz force. See Force on a charged particle below. An alternative working definition of the B-field can be given in terms of the torque on a magnetic dipole placed in a B-field. See Torque on a magnet due to a B-field below.

The B-field is measured in teslas in SI units and in gauss in cgs units. (1 tesla = 10,000 gauss). The SI unit of tesla is equivalent to (newton × second)/(coulomb × metre)[nb 6] The smallest magnetic field measured[3] is on the order of attoteslas (10−18 tesla); the largest magnetic field produced in a laboratory is 2,800 T (VNIIEF in Sarov, Russia, 1998)[4] The magnetic field of some astronomical objects such as magnetars are much higher; magnetars range from 0.1 to 100 GT (108 to 1011 T).[5] See orders of magnitude (magnetic field).

Devices used to measure the local magnetic field are called magnetometers. Important classes of magnetometers include using a rotating coil, Hall effect magnetometers, NMR magnetometers, SQUID magnetometers, and fluxgate magnetometers. The magnetic fields of distant astronomical objects can be determined by noting their effects on local charged particles. For instance, electrons spiraling around a field line produce synchrotron radiation which is detectable in radio waves.

H is defined as a modification of B due to magnetic fields produced by material media. See H and B inside and outside of magnetic materials below for the relationship between B and H. The H-field is measured in ampere-turn per metre (A/m) in SI units, and in oersteds (Oe) in cgs units.[6]

Magnetic field lines

Mapping out the strength and direction of the magnetic field is simple in principle. First, the strength and direction of the magnetic field is measured at a large number of locations. Each location is then marked with an arrow (called a vector) pointing in the direction of the local magnetic field with a length proportional to the strength of the magnetic field.

A simpler way to visualize the magnetic field is to 'connect' the arrows to form "magnetic field lines". Magnetic field lines make it much easier to visualize and understand the complex mathematical relationships underlying magnetic field. If done carefully, a field line diagram contains the same information as the vector field it represents. The magnetic field can be estimated at any point on a magnetic field line diagram (whether on a field line or not) using the direction and density of nearby magnetic field lines.[nb 7] A higher density of nearby field lines indicates a stronger magnetic field.

The direction of a magnetic field line can be revealed using a compass. The magnetic field points away from a magnet near its north pole and towards a magnet near its south pole. Magnetic field lines outside of a magnet point from the north pole to the south. This process works even for situations where there is no magnetic pole. A straight current-carrying wire, for instance, produces a magnetic field that points neither towards nor away from the wire, but encircles it instead.

Various phenomena have the effect of "displaying" magnetic field lines as though the field lines were physical phenomena. For example, iron filings placed in a magnetic field line up to form lines that correspond to 'field lines'. Magnetic fields "lines" are also visually displayed in polar auroras, in which plasma particle dipole interactions create visible streaks of light that line up with the local direction of Earth's magnetic field. However, field lines are a visual and conceptual aid only and are no more real than (for example) the contour lines (constant altitude) on a topographic map. They do not exist in the actual field; a different choice of mapping scale could show twice as many "lines" or half as many.

Field lines can be used as a qualitative tool to visualize magnetic forces. In ferromagnetic substances like iron and in plasmas, magnetic forces can be understood by imagining that the field lines exert a tension, (like a rubber band) along their length, and a pressure perpendicular to their length on neighboring field lines. 'Unlike' poles of magnets attract because they are linked by many field lines; 'like' poles repel because their field lines do not meet, but run parallel, pushing on each other.

B-field lines never end

Field lines are a useful way to represent any vector field and often reveal sophisticated properties of fields quite simply. One important property of the B-field revealed this way is that magnetic B field lines neither start nor end: They always either form closed curves ("loops"), or extend to and from infinity. (Mathematically, this means that B is a solenoidal vector field.) To date no exception to this rule has been found. (See magnetic monopole below.)

Magnetic field lines exit a magnet near its north pole and enter near its south pole, but inside the magnet B-field lines continue through the magnet from the south pole back to the north.[nb 8] If a B-field line enters a magnet somewhere it has to leave somewhere else; it is not allowed to have an end point. Magnetic poles, therefore, always come in N and S pairs. Cutting a magnet in half results in two separate magnets each with both a north and a south pole.

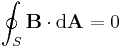

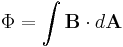

More formally, since all the magnetic field lines that enter any given region must also leave that region, subtracting the 'number'[nb 9] of field lines that enter the region from the number that exit gives identically zero. Mathematically this is equivalent to:

,

,

where the integral is a surface integral over the closed surface S. (A closed surface is one that completely surrounds a region with no holes to let any field lines escape.) Since dA points outward, the dot product in the integral is positive for B-field pointing out and negative for B-field pointing in.

There is also a corresponding differential form of this equation which is covered in Maxwell's equations below.

H-field lines begin and end near magnetic poles

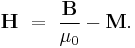

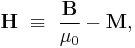

Outside a magnet, H-field lines are identical to B-field lines, but inside they can point in different directions, depending on the value of the magnetization M. This can be seen from the relationship

For example, in the absence of an externally applied magnetic field, the H-field lines inside a uniform magnet point in the opposite direction of the B-field lines. In this case, whether inside or out of a magnet, H-field lines start near the north pole and end near the south pole (the B-field lines, for comparison, form a closed loop going from south to north inside the magnet and from north to south outside the magnet). The H-field, therefore, is analogous to the electric field E which starts at a positive charge and ends at a negative charge. It is tempting, therefore, to model magnets in terms of magnetic charges localized near the poles. Unfortunately, this model is incorrect; for instance, it often fails when determining the magnetic field inside of magnets. (See "Non-uniform magnetic field causes like poles to repel and opposites to attract" below.)

Magnetic monopole (hypothetical)

A magnetic monopole is a hypothetical particle (or class of particles) that has, as its name suggests, only one magnetic pole (either a north pole or a south pole). In other words, it would possess a "magnetic charge" analogous to an electric charge.

Modern interest in this concept stems from particle theories, notably Grand Unified Theories and superstring theories, that predict either the existence, or the possibility, of magnetic monopoles. These theories and others have inspired extensive efforts to search for monopoles. Despite these efforts, no magnetic monopole has been observed to date.[nb 10]

In recent research, materials known as spin ices can simulate monopoles, but do not contain actual monopoles.

The magnetic field and permanent magnets

Permanent magnets are objects that produce their own persistent magnetic fields. They are made of ferromagnetic materials, such as iron and nickel, that have been magnetized, and they have both a north and a south pole.

Magnetic field of permanent magnets

The magnetic field of permanent magnets can be quite complicated, especially near the magnet. The B field of a small[nb 11] straight magnet is proportional to the magnets strength (called its magnetic dipole moment m). The equations involved are non-trivial and also depend on the distance from the magnet and the orientation of the magnet. For simple magnets, m points in the direction of a line drawn from the south to the north pole of the magnet. Flipping a bar magnet is equivalent to rotating its m by 180 degrees.

It is sometimes useful to model the force and torques between two magnets as due to magnetic poles repelling or attracting each other in the same manner as the Coulomb force between electrical charges. In this model, a magnetic H-field is produced by magnetic charges that are 'smeared' around each pole. A north pole therefore feels a force in the direction of the H-field while the force on the south pole is opposite to the H-field.

Unfortunately, the concept of poles of 'magnetic charge' does not accurately reflect what happens inside a magnet (see ferromagnetism). Magnetic charges do not exist. Magnetic poles cannot exist apart from each other; all magnets have north/south pairs which cannot be separated without creating two magnets each having a north/south pair. Too, a small magnet placed inside of a larger magnet is twisted in the opposite direction to that expected from the H-field. Finally, magnetic charge fails to account for magnetism that is produced by electrical currents nor the force that a magnetic field applies to moving electrical charges.

The more physically correct description of magnetism involves atomic sized loops of current distributed throughout the magnet.[7]

Non-uniform magnetic field causes like poles to repel and opposites to attract

The force between two small magnets is quite complicated and depends on the strength and orientation of both magnets and the distance and direction of the magnets relative to each other. The force is particularly sensitive to rotations of the magnets due to magnetic torque. The force on each magnet depends on its magnetic moment and the magnetic field B[nb 12] of the other.

To understand the force between magnets and to generalize it to other cases it is useful to examine the magnetic charge model given above (with the caveats given above as well). In this model, the H-field of the first magnet pushes and pulls on the magnetic charges near both poles of the second magnet. If the H-field due to the first magnet is the same at both poles of the second magnet then there is no net force on that magnet since the force is opposite for opposite poles. The magnetic field is not the same, though; the magnetic field is significantly stronger near the poles of a magnet. In this nonuniform magnetic field, each pole sees a different field and is subject to a different force. This difference in the two forces moves the magnet in the direction of increasing magnetic field and may also cause a net torque.

This is a specific example of a general rule that magnets are attracted (or repulsed depending on the orientation of the magnet) into regions of higher magnetic field. Any non-uniform magnetic field whether caused by permanent magnets or by electrical currents will exert a force on a small magnet in this way.

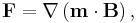

Mathematically, the force on a small magnet having a magnetic moment m due to a magnetic field B is:[8]

where the gradient ∇ is the change of the quantity m · B per unit distance and the direction is that of maximum increase of m · B. To understand this equation, note that the dot product m · B = mBcos(θ), where m and B represent the magnitude of the m and B vectors and θ is the angle between them. If m is in the same direction as B then the dot product is positive and the gradient points 'uphill' pulling the magnet into regions of higher B-field (more strictly larger m · B). This equation is strictly only valid for magnets of zero size, but is often a good approximation for not too large magnets. The magnetic force on larger magnets is determined by dividing them into smaller regions having their own m then summing up the forces on each of these regions.

Torque on a magnet due to a B-field

Magnetic torque on a magnet due to an external magnetic field can be observed by placing two magnets near each other while allowing one to rotate. Magnetic torque is used to drive simple electric motors. In one simple motor design, a magnet is fixed to a freely rotating shaft and subjected to a magnetic field from an array of electromagnets. By continuously switching the electrical current through each of the electromagnets, thereby flipping the polarity of their magnetic fields, like poles are kept next to the rotor; the resultant torque is transferred to the shaft. See Rotating magnetic fields below.

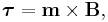

Magnetic torque τ tends to align a magnet's poles with the B-field lines (since m is in the direction of the poles this is equivalent to saying that it tends to align m in the same direction as B). This is why the magnetic needle of a compass points toward earth's north pole. By definition, the direction of the Earth's local magnetic field is the direction in which the north pole of a compass (or of any magnet) tends to point.

Mathematically, the torque τ on a small magnet is proportional both to the applied B-field and to the magnetic moment m of the magnet:

where × represents the vector cross product. Note that this equation includes all of the qualitative information included above. There is no torque on a magnet if m is in the same direction as B. (The cross product is zero for two vectors that are in the same direction.) Further, all other orientations feel a torque that twists them toward the direction of B.

The magnetic field and electrical currents

Currents of electrical charges both generate a magnetic field and feel a force due to magnetic B-fields.

Magnetic field due to moving charges and electrical currents

All moving charged particles produce magnetic fields. Moving point charges, such as electrons, produce complicated but well known magnetic fields that depend on the charge, velocity, and acceleration of the particles.[9]

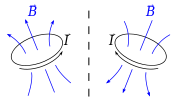

Magnetic field lines form in concentric circles around a cylindrical current-carrying conductor, such as a length of wire. The direction of such a magnetic field can be determined by using the "right hand grip rule" (see figure at right). The strength of the magnetic field decreases with distance from the wire. (For an infinite length wire the strength decreases inversely proportional to the distance.)

Bending a current-carrying wire into a loop concentrates the magnetic field inside the loop while weakening it outside. Bending a wire into multiple closely-spaced loops to form a coil or "solenoid" enhances this effect. A device so formed around an iron core may act as an electromagnet, generating a strong, well-controlled magnetic field. An infinitely long cylindrical electromagnet has a uniform magnetic field inside, and no magnetic field outside. A finite length electromagnet produces a magnetic field that looks similar to that produced by a uniform permanent magnet except that its strength and polarity are determined by the current flowing through the coil.

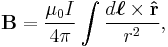

The magnetic field generated by a steady current  (a constant flow of electric charges in which charge is neither accumulating nor depleting at any point)[nb 13] is described by the Biot–Savart law:

(a constant flow of electric charges in which charge is neither accumulating nor depleting at any point)[nb 13] is described by the Biot–Savart law:

where the integral sums over the wire length where vector dℓ is the direction of the current, μ0 is the magnetic constant, r is the distance between the location of dℓ and the location at which the magnetic field is being calculated, and r̂ is a unit vector in the direction of r.

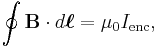

A slightly more general[10][nb 14] way of relating the current  to the B-field is through Ampère's law:

to the B-field is through Ampère's law:

where the line integral is over any arbitrary loop and  enc is the current enclosed by that loop. Ampère's law is always valid for steady currents and can be used to calculate the B-field for certain highly symmetric situations such as an infinite wire or an infinite solenoid.

enc is the current enclosed by that loop. Ampère's law is always valid for steady currents and can be used to calculate the B-field for certain highly symmetric situations such as an infinite wire or an infinite solenoid.

In a modified form that accounts for time varying electric fields, Ampère's law is one of four Maxwell's equations that describe electricity and magnetism.

Force on moving charges and current

Force on a charged particle

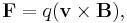

A charged particle moving in a B-field experiences a sideways force that is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field, the component of the velocity that is perpendicular to the magnetic field and the charge of the particle. This force is known as the Lorentz force, and is given by

where F is the force, q is the electric charge of the particle, v is the instantaneous velocity of the particle, and B is the magnetic field (in teslas).

The Lorentz force is always perpendicular to both the velocity of the particle and the magnetic field that created it. Neither a stationary particle nor one moving in the direction of the magnetic field lines experiences a force. For that reason, charged particles move in a circle (or more generally, in a helix) around magnetic field lines; this is called cyclotron motion. Because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the motion, the magnetic fields can do no work on an isolated charge. It can and does, however, change the particle's direction, even to the extent that a force applied in one direction can cause the particle to drift in a perpendicular direction. It is often claimed that the magnetic force can do work to a non-elementary magnetic dipole, or to charged particles whose motion is constrained by other forces, but this is not the case[11] because the work in those cases is performed by the electric forces of the charges deflected by the magnetic field.

Force on current-carrying wire

The force on a current carrying wire is similar to that of a moving charge as expected since a charge carrying wire is a collection of moving charges. A current carrying wire feels a sideways force in the presence of a magnetic field. The Lorentz force on a macroscopic current is often referred to as the Laplace force. Consider a conductor of length l and area of cross section A and has charge q which is due to electric current i .If a conductor is placed in a magnetic field of induction B which makes an angle θ with the velocity of charges in the conductor which has i current flowing in it. then force exerted due to small particle q is F = qvBsinθ then for n number of charges it has N = nlA then force exered on the body is f=FN =>f=(qvBsinθ)(nlA) but nqvA = i that is f =Bilsinθ

Direction of force

The direction of force on a charge or a current can be determined by a mnemonic known as the right-hand rule. See the figure on the left. Using the right hand and pointing the thumb in the direction of the moving positive charge or positive current and the fingers in the direction of the magnetic field the resulting force on the charge points outwards from the palm. The force on a negatively charged particle is in the opposite direction. If both the speed and the charge are reversed then the direction of the force remains the same. For that reason a magnetic field measurement (by itself) cannot distinguish whether there is a positive charge moving to the right or a negative charge moving to the left. (Both of these cases produce the same current.) On the other hand, a magnetic field combined with an electric field can distinguish between these, see Hall effect below.

An alternative mnemonic to the right hand rule is Fleming's left hand rule.

H and B inside and outside of magnetic materials

The formulas derived for the magnetic field above are correct when dealing with the entire current. A magnetic material placed inside a magnetic field, though, generates its own bound current which can be a challenge to calculate. (This bound current is due to the sum of atomic sized current loops and the spin of the subatomic particles such as electrons that make up the material.) The H-field as defined above helps factor out this bound current; but in order to see how, it helps to introduce the concept of magnetization first.

Magnetization

The magnetization field M represents how strongly a region of material is magnetized. For a uniform magnet the magnetization is equal to its magnetic moment, m, divided by its volume. More generally, the magnetization of a region is defined as the volume density of the net magnetic dipole moment in that region. The unit of magnetization M in SI is ampere-turn per meter which is identical to that of the H-field since the unit of magnetic moment is ampere-turn m2.

The magnetization M field of a region points in the same direction as the local B-field it produces and is the direction of the average magnetic dipole moment in the region. Therefore, M field lines move from near the south pole of a magnet to near its north. Unlike B, magnetization only exists inside a magnetic material. Therefore, magnetization field lines begin and end near magnetic poles.

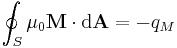

The physically correct way to represent magnetization is to add all of the currents of the dipole moments that produce the magnetization. See Magnetic dipoles below and magnetic poles vs. atomic currents for more information. The resultant current is called bound current and is the source of the magnetic field due to the magnet. Given the definition of the magnetic dipole, the magnetization field follows a similar law to that of Ampere's law: [12]

where the integral is a line integral over any closed loop and Ib is the 'bound current' enclosed by that closed loop.

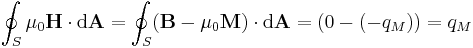

It is also possible to model the magnetization in terms of magnetic charge in which magnetization begins at and ends at bound 'magnetic charges'. If a given region, therefore, has a net positive 'magnetic charge' then it will have more magnetic field lines entering it than leaving it. Mathematically this is equivalent to:

,

,

where qM is the 'magnetic charge', S is any closed surface (one that completely surrounds a region with no holes to let any field lines escape), and the integral is a closed surface integral. The negative sign occurs because, like B inside a magnet, the magnetization field moves from south to north.

H-field and magnetic materials

The magnetic H-field differs from B in that it treats the magnetic field due to the material differently from the magnetic field due to external sources. Whereas B field lines always form loops around the total current, both the external 'free currents' and the internal 'bound currents', H re-factors the bound current in terms of 'magnetic charges'. The H field lines loops around 'free current' but it begins and ends at magnetic charges (near magnetic poles) as well.

To do this the H-field is defined as:

(definition of H in SI units)

(definition of H in SI units)

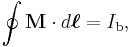

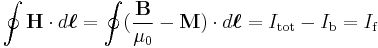

This re-factoring allows the bound sources to be isolated from the free sources. For example, a line integral of the H-field in a closed loop yields the total free current in the loop (not including the bound current):

,

,

where If represents the 'free current' enclosed by the loop.[13] For the differential equivalent of this equation see Maxwell's equations. Similarly, a surface integral of H over any closed surface is independent of the free currents and picks out the 'magnetic charges' within that closed surface:

.

.

Magnetism

Most materials respond to an applied B-field by producing their own magnetization M and therefore their own B-field. Typically, the response is very weak and exists only when the magnetic field is applied. The term 'magnetism' is used to describe how these materials respond on the microscopic level and is used to categorize the magnetic phase of a material. Materials are divided into groups based upon their magnetic behavior:

- Diamagnetic materials[14] produce a magnetization that opposes the magnetic field.

- Paramagnetic materials[14] produce a magnetization in the same direction as the applied magnetic field.

- Ferromagnetic materials and the closely related ferrimagnetic materials and antiferromagnetic materials[15][16] can have a magnetization independent of an applied B-field with a complex relationship between the two fields.

- Superconductors (and ferromagnetic superconductors)[17][18] are materials that are characterized by perfect conductivity below a critical temperature and magnetic field. They also are highly magnetic and can be perfect diamagnets below a lower critical magnetic field. Superconductors often have a broad range of temperatures and magnetic fields (the so named mixed state) for which they exhibit a complex hysteretic dependence of M on B.

In the case of paramagnetism, and diamagnetism the magnetization M is often proportional to the applied magnetic field such that:

where  is a material dependent parameter called the permeability. In some cases the permeability may be a second rank tensor so that H may not point in the same direction as B. These relations between B and H are examples of constitutive equations. However, superconductors and ferromagnets have a more complex B to H relation, see magnetic hysteresis.

is a material dependent parameter called the permeability. In some cases the permeability may be a second rank tensor so that H may not point in the same direction as B. These relations between B and H are examples of constitutive equations. However, superconductors and ferromagnets have a more complex B to H relation, see magnetic hysteresis.

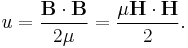

Energy stored in magnetic fields

In asking how much energy is needed to create a specific magnetic field using a particular current it is important to distinguish between free and bound currents. For example, imagine that a magnetic material is inside of an electromagnet formed of a coil of wire attached to a battery through a switch. If the switch is initially open and then is closed the magnetic field that is created is driven by the battery. In this scenario the battery is the only source of energy; and it is only doing work to the 'free current' that is flowing through the coil. (The battery does not push on the currents in the magnetic material.) The bound currents in the magnetic material create a magnetic field that the free current has to work against without doing any of the work.

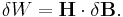

It is not surprising, therefore, that the H-field is important in magnetic energy calculations since it treats the two sources differently. In general the incremental amount of work per unit volume δW needed to cause a small change of magnetic field δB is:

If there are no magnetic materials around then we can replace H with B ⁄ μ0,

For linear, nondispersive, materials (such that B = μH where μ is frequency-independent), the energy density can be expressed as:

(Valid only for linear materials with negligible material dispersion)

(Valid only for linear materials with negligible material dispersion)

The above equation cannot be used for nonlinear materials - for these the first equation, which is always valid, must be used instead. In particular, the energy density stored in the fields of hysteretic materials such as ferromagnets and superconductors depends on how the magnetic field was created.

Electromagnetism: the relationship between magnetic and electric fields

Faraday's Law: Electric force due to a changing B-field

A changing magnetic field, such as a magnet moving through a conducting coil, generates an electric field (and therefore tends to drive a current in the coil). This is known as Faraday's law and forms the basis of many electrical generators and electric motors. The current created generates a magnetic field that tends to oppose the change in the magnetic field that induced it. This is known as Lenz's law.

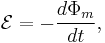

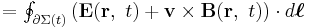

In terms of magnetic field lines, the electrical voltage that is generated in an electrically conducting coil is proportional to the time rate of change of the number of magnetic field lines that pass completely through the loop. Mathematically then, Faraday's law is represented as:

where  is the electromotive force (or EMF, the voltage generated around a closed loop) and Φm is the magnetic flux—the product of the area times the magnetic field normal to that area. (This definition of magnetic flux is why engineers often refer to B as "magnetic flux density".) The negative sign is necessary and represents Lenz's law.

is the electromotive force (or EMF, the voltage generated around a closed loop) and Φm is the magnetic flux—the product of the area times the magnetic field normal to that area. (This definition of magnetic flux is why engineers often refer to B as "magnetic flux density".) The negative sign is necessary and represents Lenz's law.

This integral formulation of Faraday's law can be converted[nb 15] into a differential form, which applies under slightly different conditions. This form is covered as one of Maxwell's equations below.

Maxwell's correction to Ampère's Law: The magnetic field due to a changing electric field

Similar to the way that a changing magnetic field generates an electric field, a changing electric field generates a magnetic field. This fact is known as 'Maxwell's correction to Ampère's law'. Maxwell's correction to Ampère's Law bootstrap together with Faraday's law of induction to form electromagnetic waves, such as light. There, a changing electric field generates a changing magnetic field which generates a changing electric field again.

Maxwell's correction to Ampère law is applied as an additive term to the Ampere's law that is given above. The additive term, similar to Faraday's law above, is proportional to the time rate of change of the Electric flux but with a different and positive constant out front. (The flux of E through an area is proportional to the area times the perpendicular part of the electric field.)

This full Ampère law including the correction term is known as the Maxwell–Ampère equation. It is not commonly given in integral form because the effect is so small that it can typically be ignored. The exception to this is the propagation and creation of electromagnetic waves which is covered in the differential form of this equation.

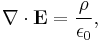

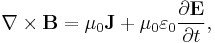

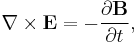

Maxwell's equations

Like all vector fields the B-field has two important mathematical properties that relates it to its sources. (For magnetic fields the sources are currents and changing electric fields.) These two properties, along with the two corresponding properties of the electric field, make up Maxwell's Equations. Maxwell's Equations together with the Lorentz force law form a complete description of classical electrodynamics including both electricity and magnetism.

The first property is the divergence of a vector field A, ∇ · A which represents how A 'flows' outward from a given point. As discussed above, a B-field line never starts nor ends at a point but instead forms a complete loop. This is mathematically equivalent to saying that the divergence of B is zero. (Such vector fields are called solenoidal vector fields.) This property is called Gauss's law for magnetism and is equivalent to the statement that there are no magnetic charges or magnetic monopoles. The electric field on the other hand begins and ends at electrical charges so that its divergence is non-zero and proportional to the charge density (See Gauss's law).

The second mathematical property is called the curl, such that ∇ × A represents how A curls or 'circulates' around a given point. The result of the curl is called a 'circulation source'. The equations for the curl of B and of E are called the Ampère–Maxwell equation and Faraday's law respectively. They represent the differential forms of the integral equations given above.

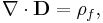

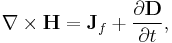

The complete set of Maxwell's equations then are:

where J = complete microscopic current density and ρ is the charge density.

Technically, B is a pseudovector (also called an axial vector) due to being defined by a vector cross product. Because of the right-hand rule, if a current-carrying loop were viewed in a mirror, the resulting B vector would be both mirror imaged and flipped in orientation, whereas an ordinary vector (e.g., velocity) would be mirror-imaged only. (See diagram to right.)

As discussed above, materials respond to an applied electric E field and an applied magnetic B field by producing their own internal 'bound' charge and current distributions that contribute to E and B but are difficult to calculate. To circumvent this problem the auxiliary H and D fields are defined so that Maxwell's equations can be re-factored in terms of the free current density Jf and free charge density ρf:

These equations are not any more general then the original equations (if the 'bound' charges and currents in the material are known'). They also need to be supplemented by the relationship between B and H as well as that between E and D. On the other hand, for simple relationships between these quantities this form of Maxwell's equations can circumvent the need to calculate the bound charges and currents.

Electric and magnetic fields: different aspects of the same phenomenon

According to the special theory of relativity, the partition of the electromagnetic force into separate electric and magnetic components is not fundamental, but varies with the observational frame of reference; an electric force perceived by one observer is perceived by another (in a different frame of reference) as a mixture of electric and magnetic forces. (Also, a magnetic force in one reference frame is perceived as a mixture of electric and magnetic forces in another.)

More specifically, special relativity combines the electric and magnetic fields into a rank-2 tensor, called the electromagnetic tensor. Changing reference frames mixes these components. This is analogous to the way that special relativity mixes space and time into spacetime, and mass, momentum and energy into four-momentum.

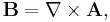

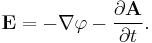

Magnetic vector potential

In advanced topics such as quantum mechanics and relativity it is often easier to work with a potential formulation of electrodynamics rather than in terms of the electric and magnetic fields. In this representation, the vector potential, A, and the scalar potential, φ, are defined such that:

The vector potential A may be interpreted as a generalized potential momentum per unit charge[19] just as φ is interpreted as a generalized potential energy per unit charge.

Maxwell's equations when expressed in terms of the potentials can be cast into a form that agrees with special relativity with little effort.[20] In relativity A together with φ forms the four-potential analogous to the four-momentum which combines the momentum and energy of a particle. Using the four potential instead of the electromagnetic tensor has the advantage of being much simpler; further it can be easily modified to work with quantum mechanics.

Quantum electrodynamics

In modern physics, the electromagnetic field is understood to be not a classical field, but rather a quantum field; it is represented not as a vector of three numbers at each point, but as a vector of three quantum operators at each point. The most accurate modern description of the electromagnetic interaction (and much else) is Quantum electrodynamics (QED),[21] which is incorporated into a more complete theory known as the "Standard Model of particle physics".

In QED, the magnitude of the electromagnetic interactions between charged particles (and their antiparticles) is computed using perturbation theory; these rather complex formulas have a remarkable pictorial representation as Feynman diagrams in which virtual photons are exchanged.

Predictions of QED agree with experiments to an extremely high degree of accuracy: currently about 10−12 (and limited by experimental errors); for details see precision tests of QED. This makes QED one of the most accurate physical theories constructed thus far.

All equations in this article are in the classical approximation, which is less accurate than the quantum description mentioned here. However, under most everyday circumstances, the difference between the two theories is negligible.

Important uses and examples of magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field

The Earth's magnetic field is thought to be produced by convection currents in the outer liquid of Earth's core. The Dynamo theory proposes that these movements produce electrical currents which, in turn, produce the magnetic field.[22] The presence of this field causes a compass, placed anywhere within it, to rotate so that the "north pole" of the magnet in the compass points roughly north, toward Earth's north magnetic pole. This is the traditional definition of the "north pole" of a magnet, although other equivalent definitions are also possible. One confusion that arises from this definition is that, if Earth itself is considered as a magnet, the south pole of that magnet would be the one nearer the north magnetic pole, and vice-versa[23] (opposite poles attract, so the north pole of the compass magnet is attracted to the south pole of Earth's interior magnet). The north magnetic pole is so-named not because of the polarity of the field there but because of its geographical location. The north and south poles of a permanent magnet are so-called because they are "north-seeking" and "south-seeking", respectively.[24]

The figure to the right is a sketch of Earth's magnetic field represented by field lines. For most locations, the magnetic field has a significant up/down component in addition to the North/South component. (There is also an East/West component; Earth's magnetic poles do not coincide exactly with Earth's geological pole.) The magnetic field can be visualised as a bar magnet buried deep in Earth's interior.

Earth's magnetic field is not constant — the strength of the field and the location of its poles vary. There is also evidence to suggest that the poles periodically reverse their orientation in a process called geomagnetic reversal.

Rotating magnetic fields

The rotating magnetic field is a key principle in the operation of alternating-current motors. A permanent magnet in such a field rotates so as to maintain its alignment with the external field. This effect was conceptualized by Nikola Tesla, and later utilized in his, and others', early AC (alternating-current) electric motors. A rotating magnetic field can be constructed using two orthogonal coils with 90 degrees phase difference in their AC currents. However, in practice such a system would be supplied through a three-wire arrangement with unequal currents. This inequality would cause serious problems in standardization of the conductor size and so, in order to overcome it, three-phase systems are used where the three currents are equal in magnitude and have 120 degrees phase difference. Three similar coils having mutual geometrical angles of 120 degrees create the rotating magnetic field in this case. The ability of the three-phase system to create a rotating field, utilized in electric motors, is one of the main reasons why three-phase systems dominate the world's electrical power supply systems.

Because magnets degrade with time, synchronous motors use DC voltage fed rotor windings which allows the excitation of the machine to be controlled and induction motors use short-circuited rotors (instead of a magnet) following the rotating magnetic field of a multicoiled stator. The short-circuited turns of the rotor develop eddy currents in the rotating field of the stator, and these currents in turn move the rotor by the Lorentz force.

In 1882, Nikola Tesla identified the concept of the rotating magnetic field. In 1885, Galileo Ferraris independently researched the concept. In 1888, Tesla gained U.S. Patent 381,968 for his work. Also in 1888, Ferraris published his research in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin.

Hall effect

The charge carriers of a current carrying conductor placed in a transverse magnetic field experience a sideways Lorentz force; this results in a charge separation in a direction perpendicular to the current and to the magnetic field. The resultant voltage in that direction is proportional to the applied magnetic field. This is known as the 'Hall effect'.

The Hall effect is often used to measure the magnitude of a magnetic field. It is used as well to find the sign of the dominant charge carriers in materials such as semiconductors (negative electrons or positive holes).

Magnetic circuits

An important use of H is in magnetic circuits where inside a linear material B = μ H. Here, μ is the magnetic permeability of the material. This result is similar in form to Ohm's law J = σ E, where J is the current density, σ is the conductance and E is the electric field. Extending this analogy we derive the counterpart to the macroscopic Ohm's law ( I = V ⁄ R ) as:

where  is the magnetic flux in the circuit,

is the magnetic flux in the circuit,  is the magnetomotive force applied to the circuit, and

is the magnetomotive force applied to the circuit, and  is the reluctance of the circuit. Here the reluctance

is the reluctance of the circuit. Here the reluctance  is a quantity similar in nature to resistance for the flux.

is a quantity similar in nature to resistance for the flux.

Using this analogy it is straight-forward to calculate the magnetic flux of complicated magnetic field geometries, by using all the available techniques of circuit theory.

Magnetic field shape descriptions

- An azimuthal magnetic field is one that runs east-west.

- A meridional magnetic field is one that runs north-south. In the solar dynamo model of the Sun, differential rotation of the solar plasma causes the meridional magnetic field to stretch into an azimuthal magnetic field, a process called the omega-effect. The reverse process is called the alpha-effect.[25]

- A dipole magnetic field is one seen around a bar magnet or around a charged elementary particle with nonzero spin.

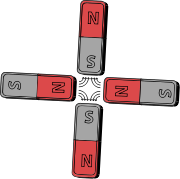

- A quadrupole magnetic field is one seen, for example, between the poles of four bar magnets. The field strength grows linearly with the radial distance from its longitudinal axis.

- A solenoidal magnetic field is similar to a dipole magnetic field, except that a solid bar magnet is replaced by a hollow electromagnetic coil magnet.

- A toroidal magnetic field occurs in a doughnut-shaped coil, the electric current spiraling around the tube-like surface, and is found, for example, in a tokamak.

- A poloidal magnetic field is generated by a current flowing in a ring, and is found, for example, in a tokamak.

- A radial magnetic field is one in which the field lines are directed from the center outwards, similar to the spokes in a bicycle wheel. An example can be found in a loudspeaker transducers (driver).[26]

- A helical magnetic field is corkscrew-shaped, and sometimes seen in space plasmas such as the Orion Molecular Cloud.[27]

Magnetic dipoles

The magnetic field of a magnetic dipole is depicted on the right. From outside, the ideal magnetic dipole is identical to that of an ideal electric dipole of the same strength. Unlike the electric dipole, a magnetic dipole is properly modeled as a current loop having a current I and an area a. Such a current loop has a magnetic moment of:

where the direction of m is perpendicular to the area of the loop and depends on the direction of the current using the right-hand rule. An ideal magnetic dipole is modeled as a real magnetic dipole whose area a has been reduced to zero and its current I increased to infinity such that the product m = Ia is finite. In this model it is easy to see the connection between angular momentum and magnetic moment which is the basis of the Einstein-de Haas effect "rotation by magnetization" and its inverse, the Barnett effect or "magnetization by rotation".[28] Rotating the loop faster (in the same direction) increases the current and therefore the magnetic moment, for example.

It is sometimes useful to model the magnetic dipole similar to the electric dipole with two equal but opposite magnetic charges (one south the other north) separated by distance d. This model produces an H-field not a B-field. Such a model is deficient, though, both in that there are no magnetic charges and in that it obscures the link between electricity and magnetism. Further, as discussed above it fails to explain the inherent connection between angular momentum and magnetism.

See also

General

- Magnetohydrodynamics – the study of the dynamics of electrically conducting fluids.

- Magnetic nanoparticles – extremely small magnetic particles that are tens of atoms wide

- Magnetic reconnection – an effect which causes solar flares and auroras.

- Magnetic potential – the vector and scalar potential representation of magnetism.

- SI electromagnetism units – common units used in electromagnetism.

- Orders of magnitude (magnetic field) – list of magnetic field sources and measurement devices from smallest magnetic fields to largest detected.

- Upward continuation

Mathematics

- Magnetic helicity – extent to which a magnetic field "wraps around itself".

Applications

- Dynamo theory – a proposed mechanism for the creation of the Earth's magnetic field.

- Helmholtz coil – a device for producing a region of nearly uniform magnetic field.

- Magnetic field viewing film – Film used to view the magnetic field of an area.

- Maxwell coil – a device for producing a large volume of an almost constant magnetic field.

- Stellar magnetic field – a discussion of the magnetic field of stars.

- Teltron Tube – device used to display an electron beam and demonstrates effect of electric and magnetic fields on moving charges.

Notes

- ↑ Technically, a magnetic field is a pseudo vector; pseudo-vectors, which also include torque and rotational velocity, are similar to vectors except that they remain unchanged when the coordinates are inverted.

- ↑ Elementary particles, such as the electron, produce their own 'intrinsic' magnetic field. This is a relativistic effect and is not due to motion of the particle, but it can be modeled for most purposes as being due to rotation of the charge(s) that make up the particle; for this reason it is called spin. The magnetic field of a permanent magnet is mostly produced by the spin of 'unpaired' electrons in the material.

- ↑ By the definition of magnetization, in this model, and in analogy to the physics of springs, the work done per unit volume, in stretching and twisting the bonds between magnetic charge to increment the magnetization by μ0δM is W = H · μ0δM. In this model, B = μ0 (H + M ) is an effective magnetization which includes the H-field term to account for the energy of setting up the magnetic field in a vacuum. Therefore the total energy density increment needed to increment the magnetic field is W = H · δB. This is the correct result, but it is derived from an incorrect model.

- ↑ In retrospect the success of this model is due largely to the remarkable coincidence that from the 'outside' the field of an electric dipole has the exact same form as that of a magnetic dipole. It is therefore only for the physics of magnetism 'inside' of magnetic material where the simpler model of magnetic charges fails.

- ↑ The standard graduate textbook by J. D. Jackson "Classical Electrodynamics" specifically follows the historical tradition, specifically, "In the presence of magnetic materials the dipole tends to align itself in a certain direction. That direction is by definition the direction of the magnetic flux density, denoted by B, provided the dipole is sufficiently small and weak that it does not perturb the existing field". Similarly, in Section 5 of Jackson, H is referred to as the magnetic field. Hence, Edward Purcell, in Electricity and Magnetism, McGraw-Hill, 1963, writes, Even some modern writers who treat B as the primary field feel obliged to call it the magnetic induction because the name magnetic field was historically preempted by H. This seems clumsy and pedantic. If you go into the laboratory and ask a physicist what causes the pion trajectories in his bubble chamber to curve, he'll probably answer "magnetic field", not "magnetic induction." You will seldom hear a geophysicist refer to the Earth's magnetic induction, or an astrophysicist talk about the magnetic induction of the galaxy. We propose to keep on calling B the magnetic field. As for H, although other names have been invented for it, we shall call it "the field H" or even "the magnetic field H." In a similar vein, M Gerloch (1983). Magnetism and Ligand-field Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0521249392. http://books.google.com/?id=Ovo8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA110. says: “So we may think of both B and H as magnetic fields, but drop the word 'magnetic' from H so as to maintain the distinction ... As Purcell points out, 'it is only the names that give trouble, not the symbols'.”

- ↑ This can be seen from the magnetic part of the Lorentz force law Fmag = (qv × B).

- ↑ The use of iron filings to display a field presents something of an exception to this picture; the filings alter the magnetic field so that it is much larger along the "lines" of iron, due to the large permeability of iron relative to air.

- ↑ To see that this must be true imagine placing a compass inside a magnet. There, the north pole of the compass points toward the north pole of the magnet since magnets stacked on each other point in the same direction.

- ↑ As discussed above, magnetic field lines are primarily a conceptual tool used to represent the mathematics behind magnetic fields. The total 'number' of field lines is dependent on how you draw the field lines. In practice, integral equations such as the one that follows in the main text are used instead.

- ↑ Two experiments produced candidate events that were initially interpreted as monopoles, but these are now regarded to be inconclusive. For details and references, see magnetic monopole.

- ↑ Here 'small' means that the observer is sufficiently far away that it can be treated as being infinitesimally small. 'Larger' magnets need to include more complicated terms in the expression and depend on the entire geometry of the magnet not just m.

- ↑ Either B or H may be used for the magnetic field outside of the magnet.

- ↑ In practice, the Biot–Savart law and other laws of magnetostatics are often used even when the currents are changing in time as long as it is not changing too quickly. It is often used, for instance, for standard household currents which oscillate sixty times per second.

- ↑ The Biot–Savart law contains the additional restriction (boundary condition) that the B-field must go to zero fast enough at infinity. It also depends on the divergence of B being zero, which is always valid. (There are no magnetic charges.)

- ↑ A complete expression for Faraday's law of induction in terms of the electric E and magnetic fields can be written as:

where ∂Σ(t) is the moving closed path bounding the moving surface Σ(t), and dA is an element of surface area of Σ(t). The first integral calculates the work done moving a charge a distance dℓ based upon the Lorentz force law. In the case where the bounding surface is stationary, the Kelvin–Stokes theorem can be used to show this equation is equivalent to the Maxwell–Faraday equation.

where ∂Σ(t) is the moving closed path bounding the moving surface Σ(t), and dA is an element of surface area of Σ(t). The first integral calculates the work done moving a charge a distance dℓ based upon the Lorentz force law. In the case where the bounding surface is stationary, the Kelvin–Stokes theorem can be used to show this equation is equivalent to the Maxwell–Faraday equation.

References

- ↑ Brown, Lesley, ed (2007). Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. II (Sixth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University press. pp. 3611.

- ↑ His Epistola Petri Peregrini de Maricourt ad Sygerum de Foucaucourt Militem de Magnete, which is often shortened to Epistola de magnete, is dated 1269 C.E.

- ↑ [1] Gravity Probe B

- ↑ "With record magnetic fields to the 21st Century". IEEE Xplore. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/freeabs_all.jsp?arnumber=823621.

- ↑ Kouveliotou, C.; Duncan, R. C.; Thompson, C. (February 2003). "Magnetars". Scientific American; Page 36.

- ↑ Magnetic Field Strength Converter, UnitConversion.org.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 255–8. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- ↑ See Eq. 11.42 in E. Richard Cohen, David R. Lide, George L. Trigg (2003). AIP physics desk reference (3 ed.). Birkhäuser. p. 381. ISBN 0387989730. http://books.google.com/?id=JStYf6WlXpgC&pg=PA381.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 438. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 222–225. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- ↑ Deissler, R.J. (2008). "Dipole in a magnetic field, work, and quantum spin". Physical Review E 77 (3, pt 2): 036609. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.77.036609. PMID 18517545. http://academic.csuohio.edu/deissler/PhysRevE_77_036609.pdf.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 266–8. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- ↑ John Clarke Slater, Nathaniel Herman Frank (1969). Electromagnetism (first published in 1947 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 69. ISBN 0486622630. http://books.google.com/?id=GYsphnFwUuUC&pg=PA69.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 RJD Tilley (2004). Understanding Solids. Wiley. p. 368. ISBN 0470852755. http://books.google.com/?id=ZVgOLCXNoMoC&pg=PA368.

- ↑ Sōshin Chikazumi, Chad D. Graham (1997). Physics of ferromagnetism (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0198517769. http://books.google.com/?id=AZVfuxXF2GsC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Amikam Aharoni (2000). Introduction to the theory of ferromagnetism (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0198508085. http://books.google.com/?id=9RvNuIDh0qMC&pg=PA27.

- ↑ M Brian Maple et al. (2008). "Unconventional superconductivity in novel materials". In K. H. Bennemann, John B. Ketterson. Superconductivity. Springer. p. 640. ISBN 3540732527. http://books.google.com/?id=PguAgEQTiQwC&pg=PA640.

- ↑ Naoum Karchev (2003). "Itinerant ferromagnetism and superconductivity". In Paul S. Lewis, D. Di (CON) Castro. Superconductivity research at the leading edge. Nova Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 1590338618. http://books.google.com/?id=3AFo_yxBkD0C&pg=PA169.

- ↑ E. J. Konopinski (1978). "What the electromagnetic vector potential describes". Am. J. Phys. 46 (5): 499–502. doi:10.1119/1.11298.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 422. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- ↑ For a good qualitative introduction see: Feynman, Richard (2006). QED: the strange theory of light and matter. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12575-9.

- ↑ Herbert, Yahreas (June 1954). "What makes the earth Wobble". Popular Science (New York: Godfrey Hammond): p.266. http://books.google.com/books?id=NiEDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA96&dq=What+makes+the+earth+wobble&hl=en&ei=C0RCTPvAEJm60gT35bCrDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=What%20makes%20the%20earth%20wobble&f=false.

- ↑ College Physics, Volume 10, by Serway, Vuille, and Faughn, page 628 weblink. "the geographic North Pole of Earth corresponds to a magnetic south pole, and the geographic South Pole of Earth corresponds to a magnetic north pole".

- ↑ Kurtus, Ron (2004). "Magnets". School for champions: Physics topics. http://www.school-for-champions.com/science/magnets.htm. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ The Solar Dynamo, retrieved Sep 15, 2007.

- ↑ I. S. Falconer and M. I. Large (edited by I. M. Sefton), "Magnetism: Fields and Forces" Lecture E6, The University of Sydney, retrieved 3 Oct 2008

- ↑ Robert Sanders, "Astronomers find magnetic Slinky in Orion", 12 January 2006 at UC Berkeley. Retrieved 3 Oct 2008

- ↑ (See magnetic moment for further information.) B. D. Cullity, C. D. Graham (2008). Introduction to Magnetic Materials (2 ed.). Wiley-IEEE. p. 103. ISBN 0471477419. http://books.google.com/?id=ixAe4qIGEmwC&pg=PA103.

Further reading

Web

- Nave, R.. "Magnetic Field Strength H". http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/magnetic/magfield.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- Oppelt, Arnulf (2006-11-02). "magnetic field strength". http://searchsmb.techtarget.com/sDefinition/0,290660,sid44_gci763586,00.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- "magnetic field strength converter". http://www.unitconversion.org/unit_converter/magnetic-field-strength.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

Books

- Durney, Carl H. and Johnson, Curtis C. (1969). Introduction to modern electromagnetics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-018388-0.

- Rao, Nannapaneni N. (1994). Elements of engineering electromagnetics (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-948746-8. OCLC 221993786.

- Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- Jackson, John D. (1999). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X. OCLC 224523909.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0810-8. OCLC 51095685.

- Furlani, Edward P. (2001). Permanent Magnet and Electromechanical Devices: Materials, Analysis and Applications. Academic Press Series in Electromagnetism. ISBN 0-12-269951-3. OCLC 162129430.

External links

Information

- Crowell, B., "Electromagnetism".

- Nave, R., "Magnetic Field". HyperPhysics.

- "Magnetism", The Magnetic Field. theory.uwinnipeg.ca.

- Hoadley, Rick, "What do magnetic fields look like?" 17 July 2005.

Field density

- Jiles, David (1994). Introduction to Electronic Properties of Materials (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-412-49580-5.

Rotating magnetic fields

- "Rotating magnetic fields". Integrated Publishing.

- "Introduction to Generators and Motors", rotating magnetic field. Integrated Publishing.

- "Induction Motor – Rotating Fields".

Diagrams

- McCulloch, Malcolm,"A2: Electrical Power and Machines", Rotating magnetic field. eng.ox.ac.uk.

- "AC Motor Theory" Figure 2 Rotating Magnetic Field. Integrated Publishing.

Journal articles

- Yaakov Kraftmakher, "Two experiments with rotating magnetic field". 2001 Eur. J. Phys. 22 477-482.

- Bogdan Mielnik and David J. Fernández C., "An electron trapped in a rotating magnetic field". Journal of Mathematical Physics, February 1989, Volume 30, Issue 2, pp. 537–549.

- Sonia Melle, Miguel A. Rubio and Gerald G. Fuller "Structure and dynamics of magnetorheological fluids in rotating magnetic fields". Phys. Rev. E 61, 4111 – 4117 (2000).

|

|||||